It’s a rainy(ish) day in DC, after a too-hot, too-dry summer, and the plants in my garden are loving it. I can almost hear their relief, though we need a lot more rainy days to make up the summer deficit. Everything’s dry, parched, hanging on for liquid relief.

I spent a good portion of my July and August days out in the garden, usually early in the morning or late at night to escape the punishing heat. Much of my garden routine this summer revolved around water: scrubbing out and refreshing the water features (three shallow saucers—one with a bubbler, two with water wigglers—and one mister arrangement for avian and other wild neighbors).

These unfancy fixtures take maintenance. The robins, messy and enthusiastic bathers, displace water like that guy at the community pool who cannonballs in and splashes everybody. They also tend to poop in the water, so on the hottest, driest days I’m out there multiple times, armed with the pitcher and the hose, like an overworked cabana attendant. Hard work, rewarded every time I sit on the back deck or look out the window and see robins, catbirds, wrens, sparrows, cardinals, mockingbirds, finches, and others about to take a dip or a sip. (The squirrels love it too.)

I do the work for joy, yes, but also out of a sense of obligation. The summer wouldn’t be this hot and dry if humans had done a better job of tending things. (I think about Saruman’s banger of a line from “The Fellowship of the Ring,” about the dwarves delving too greedily and too deep.) I can retreat into the AC; the robins and squirrels don’t have that luxury. I can at least make sure they have clean water to cool off in.

That’s also why I have been, over the last few years, adding more native plants to my smallish Capitol Hill rowhouse yard. My garden style is more line cook than master chef: I don’t need a Michelin star, I just want to give wild residents and visitors a place to take a break and get a decent meal, maybe find shelter too if they want it. It doesn’t have to be fancy, it just needs to offer some basic amenities. I’m a staff of one, I do what I can, with occasional help from my spouse and offspring, but I’m always learning, too, season to season, as some plants thrive (huzzah for the purple coneflower, the mountain mint, and the late-blooming boneset!) and others wither, either because they and the site don’t agree or because I’ve put them in the wrong spot. Apologies, friends. I’ll try to do better next year.

On balance I’ve had more wins than losses—at least the customers haven’t complained so far—though as with writing, it can be hard sometimes to define success. There’s a mantra among native-plant gardeners: The first year they sleep, the second year they creep, the third year they leap.

Be patient, in other words. I am not often enough patient, but plants have their own needs and timetables. So I plant and water and weed and wait to see what happens.

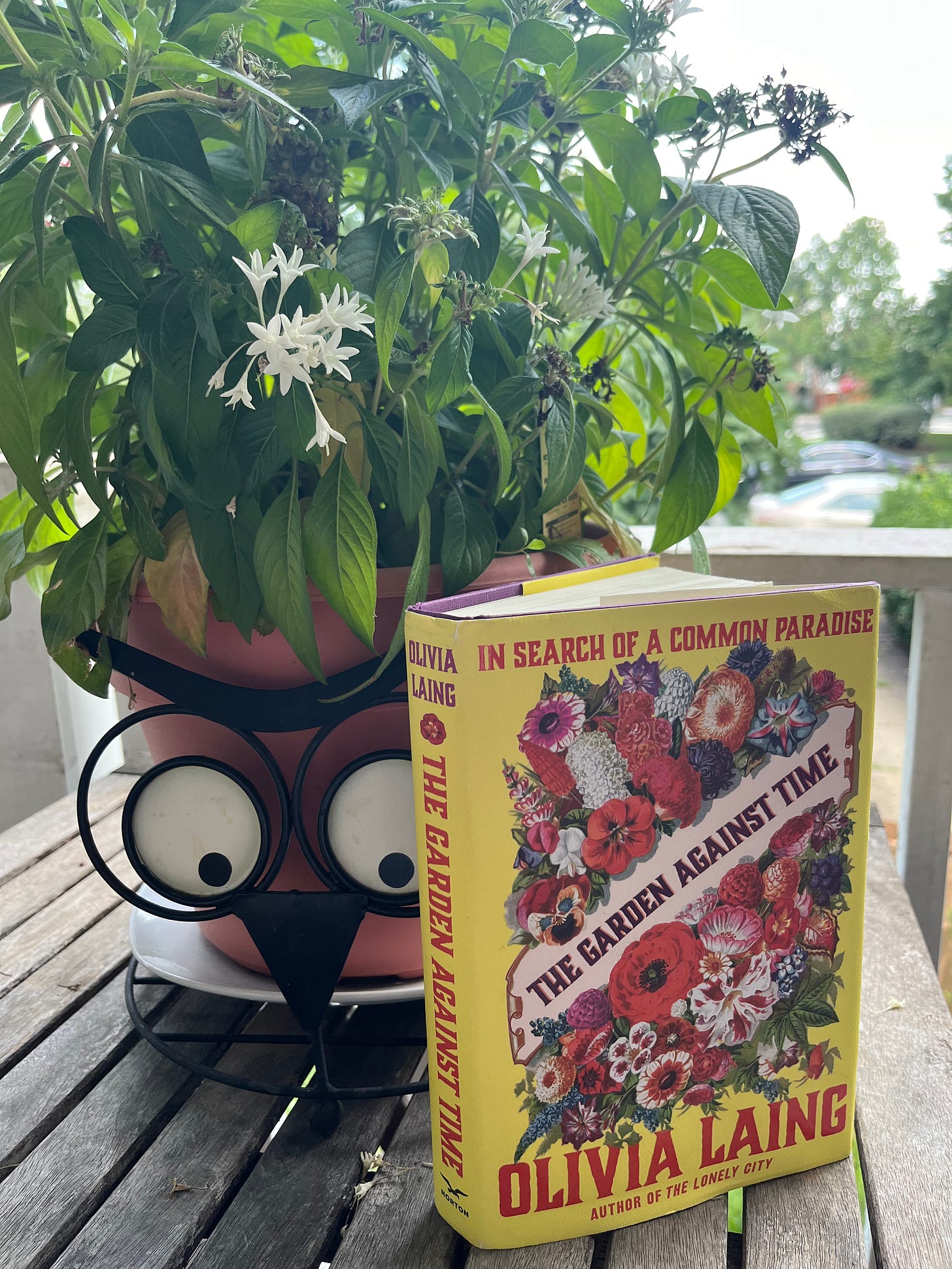

One book I read this summer spoke to me as a gardener and as a writer: The Garden Against Time: In Search of a Common Paradise by Olivia Laing. In her forties, Laing and her husband bought a historic house with a walled garden in Suffolk. The house had previously been owned by landscape designer Mark Rumary (a new name to me, but apparently well known in those circles), and Laing spent much of the pandemic delving and digging and planting to restore and update Rumary’s green vision. It’s hard labor (my back ached in sympathy) but a labor of love, a passion project, an almost obsessive commitment.

When Laing’s not found in the garden, she’s up to the elbows in literary-historical digging: into the lore behind the Garden of Eden (“I’d once heard it called the English heresy, that paradise can be located in a garden, but actually it was where the rumour of paradise was founded”); how enslaved labor from sugar plantations built the fortunes that paid for many of England’s great-house gardens; Derek Jarman’s Modern Nature, the filmmaker’s account of the iconoclastic seaside garden he cultivated while dying of AIDS; my old friend William Morris, who “believed that it was people’s right to live in beautiful, unspoilt, unpolluted places, and he thought, like Ruskin, that beauty was not a luxury”; the work and life of the poet John Clare, a true lover of wild places and the things that once grew there, and how the enclosure laws of the 18th- and 19th-centuries drove folk like him out of their Edens.

Laing draws from that literary seed bed to plant a lovely vision of gardens as communal spaces that should not be walled, private paradises, though in practice it would be unworkable or unwise to have people traipse through hers at will. (It wouldn’t work well in my rowhouse yard either, TBH.) And while she mentions a few of the animals that make a home in her garden, they feel like surprises or extras rather than stars. That, along with her devotion to cultivars and highly bred tulips and roses and other species, felt alien to me. I don’t know enough about the biomes of the British isles and what’s native there to weigh her choices in terms of biodiversity and supporting wildlife, but I finished the book with the sense that Laing’s garden principles put people first. Unlike my garden, hers is a work of art. There’s room for both.

A garden story from NYC: Students at P.S. 130, an elementary school in lower Manhattan, have been writing to NYC’s mayor to save the Elizabeth Street Garden, which I’ve never been to but which sounds like a gem of urban green space. More power to these kids (and to anybody who defends such places):

“In an effort to save their urban oasis, students in first through fourth grade have been writing letters to Mayor Eric Adams, pleading with him to save the garden. The handwritten letters, which were shared with a reporter from The New York Times, are being sent to the mayor’s office this week, said Joseph Reiver, Elizabeth Street Garden’s executive director. They are filled with endearing misspellings, grammatical errors and wobbly penmanship. But while they may appear juvenile or naïve, the issues they raise are anything but. In their messages, the students touch on themes of climate change and mental health, stressing the importance of green space and clean air.”

Book deals: There’s a great Kindle deal right now on the ebook of Clutter: An Untidy History—a steal at $2.99. Buy the ebook and you won’t have to worry about adding to your already overloaded bookshelves. (Don’t @ me about digital clutter.) And Highbridge Audio, which produced the audio version, has a 50% off promotion through Oct. 11, 2024, which means you can get the audiobook for only $10. If you prefer to buy it in print or borrow it from the library, I’d love that too.

Notes from the day job: Some of you know that I work as a book editor in addition to doing my own writing. (Bills must be paid, and I like the work.) It's always neat to see a title I worked on out in the world; the most recent one, David M. Rubenstein’s The Highest Calling: Conversations on the American Presidency (Simon & Schuster), came out Sept. 10. I’ve worked on several of his books, and this one couldn't be timelier. It includes interviews with a number of well-known presidential historians and journalists as well as conversations with several of the living presidents. As I edited, I learned quite a bit about the highs and lows of the American presidency since the founding, which has helped me find a little much-needed perspective during our recent political upheavals.

Applying to things: My alma mater required most undergrads to write a senior thesis, which turned out to be great training for the line of work I went into. A bunch of us decided to get a little cheeky and include the line “In order you win, you have to enter” somewhere in our theses. (Footnotes counted.) This fall I’ve reupped it as a motto in order to to motivate myself to apply for fellowships and residencies with fall/winter deadlines. The process of pulling together materials and writing artist’s statements has already been useful in helping me structure my current project. That, along with finding the confidence to apply, feels like a win, long though the odds are. (And they are.) If you’ve been unsure about whether to throw your hat in the ring for something you think you might qualify for, why not go for it if you can? As 21-year-old me would have said, in order to win, you have to enter. (Exceptions made for MacArthur fellows and Nobel Prize winners.)

Reading: I just started The Light Years by Elizabeth Jane Howard (no relation, as far as I know). It’s the first novel in the Cazalet Chronicles, an “Upstairs, Downstairs”-esque saga that follows various members of a well-bred English family (and their servants) from the 1930s on. H/t to my friend and publisher Anne Trubek, whose Bluesky posts about the series led me to it. And I just finished Kelly Link’s short-story collection White Cat, Black Dog, eerie recastings (very loose ones) of fairy tales. I now understand why so many people are fans of hers (don’t start, as I did, with her novel, The Book of Love), but Link’s loose approach to the source material made me appreciate Angela Carter’s versions even more.

Watching: The new seasons of Only Murders in the Building and Slow Horses (joint viewing with my spouse) and S2 of The Rings of Power (when I geek out solo).

Thanks for reading!

Cheers,

Jen

I am a huge Cazalet chronicles groupie. You might have inspired me to start over, for probably the third time. I like the look of the new editions.